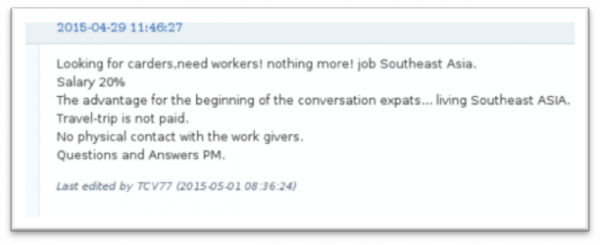

First of all, the underground recruitment industry is about far more than simply hiring developers. In order to profit, there must be an ecosystem of malware writers, exploit developers, bot net operators, and mules. Figure 1-2, for example, illustrates the huge demand for carders, individuals who traffic in stolen credit card data. To get capable individuals who can be trusted is difficult and requires a rigorous application procedure.

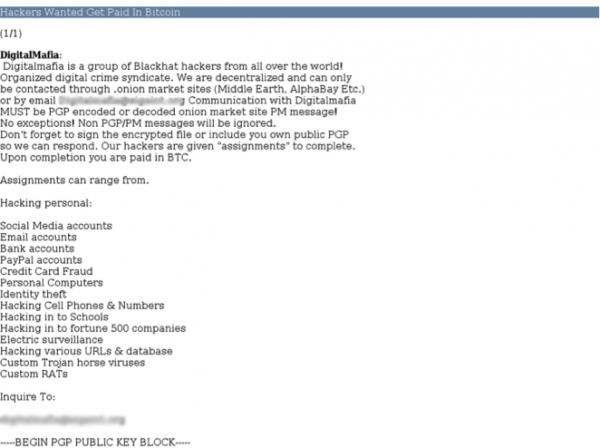

Fig 1-1: A post by a “‘digital crime syndicate” seeking hackers for their group.

Recruitment in the underground is startling in its similarities with its legitimate counterpart. While many advertisements are standalone or posted on forums, some exist on specific job boards that have been created for this express purpose. A handful of these job boards actually offer paid job advertisements; simply pay the fee and your advertisement will reach a wider audience.

Fig 1-2: A post on a carding forum, seeking individuals to help with the heavy lifting.

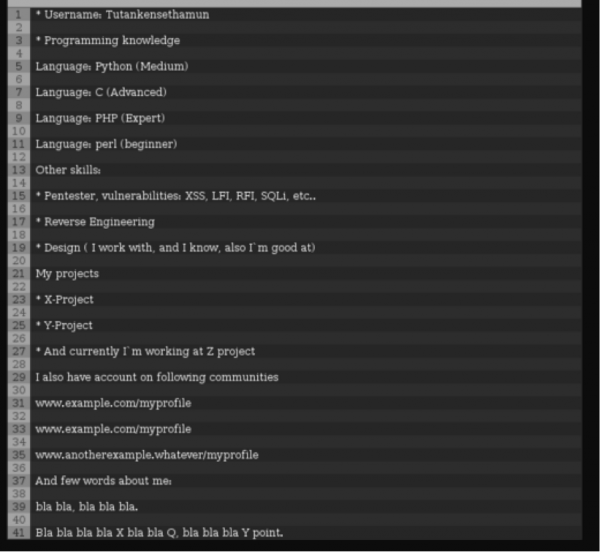

Like defenders, adversaries struggle to find qualified candidates. On forums, the frequent references to skids – “script kids” – alludes to a frustration with the lack of talent. Skids, who possess no legitimate technical skill, must be put through a rigorous process to ensure they are up to the task. There are many instances of recruiters asking for application forms – some even offer an application template. Just like in corporate cyber security hiring, bringing the wrong candidate on board wastes limited resources. Due diligence is required to ensure that only qualified candidates continue through the hiring process.

Fig 2: An example application form posted on a dark web forum.

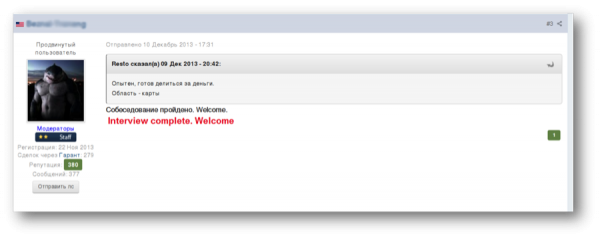

Should the initial application be successful, it is not uncommon for the candidate to be asked to complete an interview. Skype appears to be a popular tool for this, so long as users’ voices are masked, video is turned off and traffic is ported through services such as Tor. Figure 3 shows the result of a successful interview, simply stating “Interview complete. Welcome.” So that’s it? You’re in? Not necessarily.

Fig 3: A post declaring the successful completion of an interview on a Russian-speaking forum on the clear web.

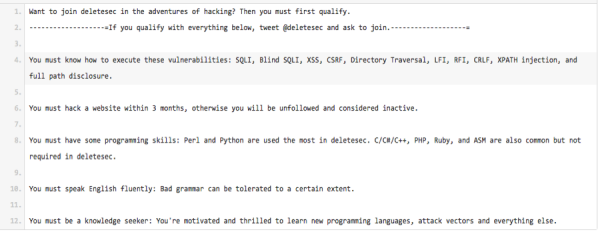

Simply having the right skills on a cyber criminal resume isn’t sufficient. Those doing the hiring may want to further vet the individual before continuing. In some instances the group insists on a probationary period, just like in corporate IT. Take Figure 4, for example, a job advertisement by a group called DeleteSec states members “must hack a website within 3 months” otherwise they will be “unfollowed and considered inactive.” Even after this probationary period, membership may not be assured.

Fig 4: A post on Pastebin by DeleteSec outlining required skill sets.

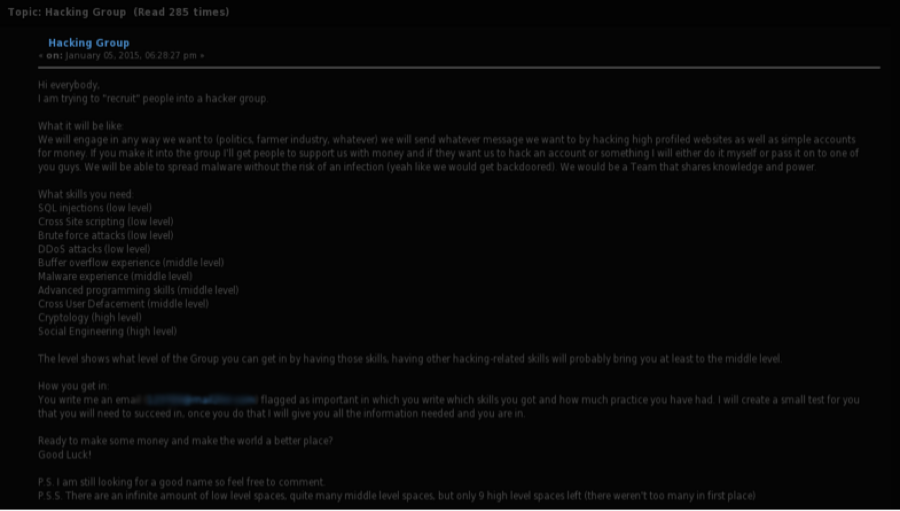

These parallels with the recruiting and hiring processes defenders follow are interesting, but the real value for organizations is in understanding what skills these actors are looking for. Take Figure 5 as an example. We can learn that there is a new group planned that intends to “hack high-profile websites as well as simple accounts,” and is “ready to make some money...” There’s also an insight into their TTPs. Skills that the group’s founder is seeking include: distributed denial of service (DDoS), social engineering, cross-site scripting (XSS) and SQL injection (SQLi). After all of these years, the fact that XSS and SQLi persist is an indictment on the security community – but that’s a topic for another blog post. The lesson is that attackers gladly go after these basic vulnerabilities and can hire those with more entry-level technical skills to boost profits even further.

There are also other, more specific requirements that attackers seek, such as insider knowledge of an organization’s operating system. Organizations with abilities to find such advertisements have an added advantage in their asymmetric battle with their adversaries.

Fig 5: A post on a dark web forum from an individual seeking to form a hacker group.

Attackers and defenders have more in common than some might think. Each group has a mission to accomplish and the success of that mission is predicated on the ability to hire and retain staff. When it comes to cybercriminals, they must find a balance between Operations Security (OPSEC) and the ability to recruit. Too much OPSEC leaves little time to identify qualified candidates, so cybercriminals make sacrifices in their path toward profit.

When attackers make these sacrifices, they leave behind clues that defenders can take advantage of to build resiliency into their security programs. In some circumstances, defenders might find specific details about attacks targeting their organization, while in others they might find general attack trends that could bolster their defenses. At the end of the day, tracking the adversary that is recruiting and the skills they most desire can improve the overall maturity of an organization’s security program and make that new recruit’s job that much harder.

DigitalShadows